|

PRODUCT

CATEGORIES

CLICK BUTTON

|

|

|

TEXAS GLORY

AS

HISTORY

-

THE

1835

CAMPAIGN

Or, How Austin and Cos

Played

the Game

By Carl Willner

This campaign history describes how the historical

1835 campaign of the Texan Revolution, from the weeks of October 7

through December 14 (Turns 1-10), when General Cos surrendered his last

garrison at the Alamo and withdrew under parole to Laredo, would have

corresponded with the TEXAS GLORY game. The history covers the

various actions permitted by the cards, taking into account all

movement of land units, including movement by sea, and all battles that

occurred during the period of the 1835 campaign of the Texan

Revolution. The specific events on the action cards are assigned

to a particular turn where a unique event clearly occurred that turn

(e.g., Surprise, Deguello). The effects of supply on

individual units are not always identified on a turn-by-turn basis, but

are discussed in broader terms by turns and over the course of the

campaign. It is not always possible to recreate the historical

events exactly as they occurred in game terms, given the unavoidable

limits of what is possible in a playable game, but the game allows the

general course of all the principal events of the campaign to be

repeated. Particularly in the 1835 campaign, the

revolutionary Texan army was very loosely organized as it was in the

process of forming, and the roles of officers shifted over time, so

that the individual units represented here for the Texans can only

approximate what occurred in real life.

Click

here to order Texas Glory now.

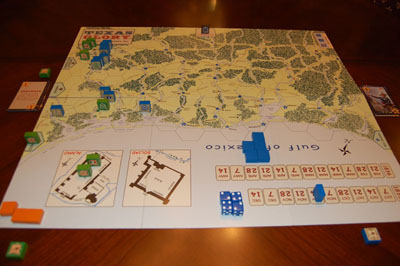

1835 Game Set up.

All

pictures can be expanded by clicking on them.

The small navies of Texas and Mexico are not

represented by units in the game. Historically, the Texan fleet

began forming during this period and there was at least one battle

between individual Texan and Mexican warships, on Turn 6 off Matagorda,

though no fleet actions. Mostly, the Texan navy was engaged

in privateering against Mexican commerce in the Gulf of Mexico, and the

Mexican navy was trying to protect its commerce and intercept the Texan

“pirates.”

During all turns, there was some movement by the

Texan forces, though the Mexicans did not always move, so that it does

not appear that the Storm event occurred. Events that can be

considered certain or likely to have been played within the context of

the “historical” game include Surprise, Runaways, and

Deguello. In light of the historical movements, the total

types of cards likely used, in game terms, are 2 4 CPs, 6 3 CPs, 6 2

CPs, and 6 1 CPs (including Surprise, Deguello and Runaways).

Unused cards include 2 0 CPs (Storm, Comanche), 1 4 CP, 1 2 CP, and 1 1

CP (Local Guide).

During 1835, no towns were burned by either side,

even though they could have done so. In game terms, the Mexicans

have no incentive to do so in 1835 as long as they have a hope of

retaining the Mexican-friendly green towns they hold at the start,

reflected in the game by the 1835 victory conditions which require the

Mexicans to control at least four unburned towns to win (out of the

four green towns in Texas and the three Mexican holding boxes), and

also by the ability of the Mexicans in a campaign game to use these

towns again as supply sources once recaptured in 1836. In a

campaign game, towns burned in 1835 would not have to be retaken by the

Mexicans in 1836, but keeping the towns and winning the 1835 portion of

the campaign would leave the Mexican with more blocks and better

positions at the start of 1836. The Texans might burn green

towns to avoid the necessity of leaving garrisons to hold them once

captured and eliminate the risk of Mexican recapture in 1835, but this

would also deprive the Texans of the ability to use the towns as supply

sources in 1835 and as places where Texan reinforcements can be brought

in closer to the front once Texan-controlled, rather than in the

Texan-friendly blue towns further back. Also, in a campaign

game, if the Texans burn green towns in 1835 they simply reduce the

number of towns that the Mexicans have to capture from them to win in

1836.

The Battle of Gonzales that began the Texan

Revolution, the “Lexington and Concord” of Texas, historically took

place just before the start of the first turn of the game, on October

2. In late September 1835, the Mexican commander in Texas

at the time, Col. Domingo de Ugartechea, sent a force of 100 dragoons

under Lt. Francisco Casteñeda (represented by the Alamo cavalry)

to

Gonzales, in an effort to recapture a cannon given to the settlers

earlier for protection from hostile Comanches. There, the Mexican

cavalry skirmished initially with a small body of local militia at the

ford, and later on October 2 with a quickly gathered force of 180

Texans, including 50 mounted men (represented by a unit of Texan

Militia infantry and the Kimball cavalry). The Mexican cavalry

was driven off with few losses on either side – one or two Mexicans

killed, and a Texan with a bloody nose due to falling from his horse –

and returned to San Antonio.

The campaign begins just as General Martin Perfecto

de Cos, who had arrived at Copano on September 20 with the permanente

Morelos battalion, has completed his march through Goliad up to San

Antonio and assumed command from Col. Ugartechea, who remained as his

principal subordinate. Altogether Cos has less than 1000 men

under his command, consisting of his one regular battalion and 11

companies of presidial or militia troops, mostly concentrated at San

Antonio and the Alamo with two other smaller garrisons at

Lipantitlan/San Patricio and Goliad. These Mexican forces are

inadequate to repress a rebellion by a Texan population of some 30,000,

and Cos adopts a relatively passive strategy of seeking to hold the key

strongpoints in the Mexican-populated area of Texas until Santa Anna

can send him stronger reinforcements. Historically, the local

Tejanos did not play as active a combat role on the Mexican side in

1835 as they did in 1836, as many Tejanos in 1835 still thought they

were fighting for their rights under the federalist Mexican

constitution of 1824 against an oppressive central government.

Some Tejanos sympathized with the central government even in 1835 and

spied for Cos, and there were pockets of loyalists, represented in 1835

by Carlos de la Garza and his rancheros, the Garza Tejano unit based at

Carlos.

Now that hostilities are inevitable, the Texans have

begun to form an army at Gonzales and choose Stephen Austin, the leader

of the colony, as their General, despite his lack of military

experience (historically, this takes place during the first turn of the

game, but Austin appears on the map at the start rather than as a

reinforcement to ensure that he is available to the Texans as

CinC). Meanwhile, Capt. George Collinsworth’s Texan militia

from Matagorda and other places have begun to assemble at Victoria as

well, preparing to launch an attack on the weakly garrisoned presidio

of Goliad. They are joined on their march to Goliad by the

inspiring Ben Milam, who has formerly served in the Mexican army and

has just escaped from a Mexican jail.

Turn 1 (October 7) - The

Capture of Goliad.

The Texan

gains initiative, using a Surprise event giving 1 CP, while the

Mexicans also have available 1 CP (but likely not more given their

passive opening). Milam moves from Victoria to Goliad

before the Mexicans can reinforce the garrison. The Mexicans do

not attempt to relieve Goliad with the Lipantitlan cavalry or the

Tejanos in range, but merely move the Alamo cavalry from San Antonio to

Casablanca to cover Carvajal Crossing, protecting San Antonio from the

south. Milam then storms Goliad, and with the benefit of Surprise

fires before the Mexican artillery, which would normally go first (A

vs. B) can do so. Milam scores two hits on the first round, which

with double defense eliminates one step of the Goliad artillery.

The artillery surrenders with only one step remaining, and is converted

into the corresponding Texan artillery unit. Neither side faces

any risk of supply attrition. The Texans receive Horton (1 step)

as a reinforcement at Goliad.

In the 1835

scenario, the Horton unit represents Ira Westover’s dragoon cavalry,

some 35-40 men. Goliad fell to the Texans on the night of Oct.

9-10, with around 125 Texan militia attacking against a Mexican

garrison of some 27 men (and a few others at outposts in the area, but

not more than 40-50 total) commanded by Lt. Col. Francisco

Sandoval. The battle was over in less than 30 minutes. The

Texans had only one man wounded, while the entire Mexican garrison was

captured, with a few having been wounded. The Mexican

officers were taken to San Felipe and later

paroled.

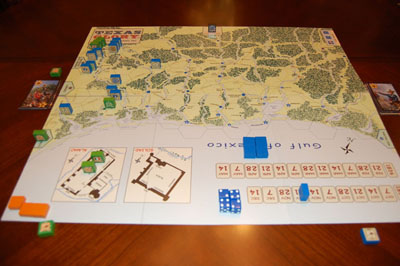

| 1835

Turn 1 Movement |

1835

Turn 1 Battle at Goliad |

|

|

| 1835

Turn 1 End |

|

|

|

Turn 2 (October 14) -

Texans Begin Their Advance on San

Antonio.

The Texan again gains initiative, with 3 CPs,

while the Mexican has available 2 CPs (which end up going

unused). The Texans make two moves: 1) Austin is activated and he

with his small army, including the Militia infantry and Kimball,

advances from Gonzales along the road toward the Alamo and San Antonio,

stopping at the river before the Tonkawa Indian village, and Kimball

pushes north of the road across the forest hexside, remaining in

Austin’s command radius; and 2) Milam moves up from Goliad along the

trail to Carvajal Crossing, and crosses the ford to Casablanca.

The Texans also forage and gain 1 step added to the Goliad artillery to

bring it up to full strength. There is only one potential battle,

and the Mexican Alamo cavalry chooses to retreat from Casablanca to the

Alamo along the trail in the first round rather than fight Milam, which

it can do as both units are Bs. Neither the Texans nor the

Mexicans face any risk of supply attrition given their

deployments. The Texans receive Seguin (1 step) as a

reinforcement at Goliad.

In the 1835 scenario, the

Kimball unit represents

the mounted Gonzales Lancers (which as their name suggests came from

Gonzales, as did Kimball’s company in 1836). The Texans

historically left Gonzales on Oct. 12, the end of the previous week, to

begin their march to San Antonio. Milam, now formally promoted to

Captain (though many of the volunteers recognized him as a Colonel),

was commanding a scout company during Austin’s advance to San Antonio

when he separately encountered the Mexican cavalry at Cibolo

Creek.

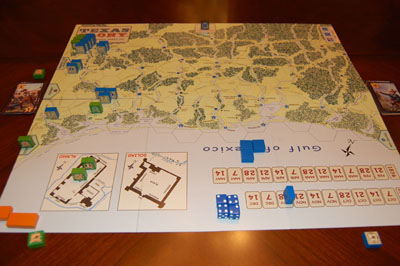

| 1835

Turn 2 Movement |

1835

Turn 2 End |

|

|

Turn 3 (October 21) -

Texans Approach San Antonio.

The Texan again gains initiative, with 2 CPs (one of which goes

unused), while the Mexican has available 1 CP (which also goes

unused). The Texans are not yet prepared to advance to San

Antonio and are waiting to build up their army, but they make one

individual move: Seguin moves up to Casablanca from Goliad to join

Milam. The Mexicans take no action. There are no

battles. Neither side faces any supply difficulties. The

Texans receive Bowie (2 steps) as a reinforcement at Gonzales.

Historically, Jim Bowie

joined

the Texan army on

October 19, serving as an elected Colonel of the volunteers, and Capt.

Juan Seguin soon afterward. The Army of Texas under Austin around

this time consisted of 453 men in 11 companies, considerably

outnumbered by Cos’s forces in San Antonio and the

Alamo.

| 1835

Turn 3 Movement |

1835

Turn 3 End |

|

|

Turn 4 (October 28) - The

Battle of Concepcion.

The Mexican

gains initiative with 3 CPs while the Texan also has available 3

CPs. The Mexicans make three moves: 1) the Lipantitlan cavalry

moves up the Atascosito Road to just before Goliad; 2) the Tejanos move

from Carlos to Refugio; and 3) the Alamo artillery is shifted from the

Alamo into San Antonio. Cos is expecting the Texans to move

against the Alamo and San Antonio now, and hopes to distract them with

a threat to Goliad, while he already has a strong force of three units

assembled at the Alamo, including himself, the Morelos infantry and the

Alamo cavalry, leaving the San Antonio presidial troops and the Alamo

artillery to garrison the city against any Texan move in that

direction. The Texans then make three moves: 1) Austin is

activated, and moves with the Militia infantry up to the Alamo, sending

Kimball also to the Alamo through the river ford at Comal Springs

(making this route of retreat available to the Texans if the upcoming

battle goes badly), and bringing Bowie, who was also in Austin’s

command radius at Gonzales, up to the Alamo along the road from

Gonzales; 2) Seguin makes an individual move up from Casablanca to the

Alamo (making this route of retreat also available to the Texans for

the upcoming battle); and 3) the Horton unit moves from Goliad around

the Mexican cavalry by the trail to San Patricio and enters

Lipantitlan. The Texans, with Austin (2 steps), the Militia

infantry (2 steps), Bowie (2 steps), Kimball (1 step) and Seguin (1

step), a total of 8 steps, are now confronting a Mexican force

consisting of Cos (2 steps), Morelos (4 steps), and the Alamo cavalry

(2 steps), also 8 steps. The Alamo artillery, even if kept at the

Alamo, would not have been able to participate in the battle fought

outside the fort, as the Mexicans initially choose to do in order to

try to prevent a siege, nor could the artillery suffer adverse effects

from the battle in the open, as artillery in a fort hex is always

considered to be defending inside the fort (it could support a Sally

from the fort, but the Alamo is not yet besieged). In the first

round of the Battle of Concepcion, Seguin fires first (A), followed by

the Alamo cavalry and Cos (Bs), then Austin and Kimball (also Bs, but

attacking), then Morelos (C) and finally Bowie and the Militia

infantry (Cs, attacking). The Texans, remarkably, suffer no

losses from the initial round of Mexican fire, while Bowie inflicts a

hit on Morelos, bringing the Mexicans down to 7 steps. Though the

Mexicans could still decide to defend in the open and hope to prevent a

siege, with most of their forces remaining, the Texans have sufficient

alternate retreat routes to avoid any loss of units, and the Mexicans

are outgunned with Bowie in the field and decide to minimize their own

losses. In the second round, the Mexicans retreat, most of their

units withdrawing back inside the Alamo while the Alamo cavalry goes to

San Antonio, suffering no further losses (only Seguin can fire before

any of the Mexicans retreat, and only Austin and Kimball can fire

before the Mexican infantry retreats, while Bowie and the Militia have

no chance to fire again before the Mexicans escape). The Alamo is

besieged, but the Texans choose not to follow up with a storming

attack, which would likely suffer heavier losses. The Texans are

now at some risk of supply attrition, with 5 units outside the Alamo (2

units above supply limits), while the Mexicans inside the Alamo are not

with only 2 units there, nor do they have supply problems with the 3

units in San Antonio. The Texans receive Fannin (2 steps)

as a reinforcement at Goliad.

In the 1835 scenario,

Capt.

James Fannin was serving

under Col. Bowie’s command at the battle of Concepcion at this

time. The Fannin unit represents the previous Texan garrison

commander of Goliad, Capt. Philip Dimmitt, until he is replaced by

Fannin during the winter, after Fannin was promoted to Lieutenant

Colonel in charge of the Texan “First Artillery” regiment.

Lt. William Travis also fought at the Battle of Concepcion as a junior

cavalry officer in charge of a mounted company. On October 27

Austin authorized Travis to raise a company of 50 mounted volunteers

from the army, and Travis led his first charge after the retreating

Mexicans in this battle. The Mexicans suffered by their own

admission 48, and more likely 76, killed and wounded at the Battle of

Concepcion, along with 1 cannon captured, out of the approximately 400

cavalry and infantry supported by some light artillery that they had

engaged, while the Texans lost only 1 man killed and 1 wounded

out of Bowie’s force of 92, thanks to the firepower of Bowie’s Kentucky

rifles. The quality of the Mexican gunpowder, in contrast, was so

poor that Texans reported Mexican bullets bouncing off their

bodies. As the rest of Austin’s army came up to reinforce Bowie,

who had been in an isolated position at the Concepcion mission, the

Mexicans lost heart and retreated, abandoning one of their 4 lb. field

pieces to the Texans. After the battle was won in the field,

Austin favored an immediate assault on the Mexican positions while the

Mexicans were still disorganized, but he was deterred by Bowie and the

other officers who reasonably expected that far greater losses would be

suffered attacking a fortification supported by artillery. Cos

still had at least 650 men available with 12 cannon at this time, even

after his battle losses. The Texan provisional government

was also formed at this time, meeting on November 3 in San Felipe, and

began to form a Texan navy from

privateers.

| 1835

Turn 4 Movement |

1835

Turn 4 Battle at the Alamo

|

|

|

| 1835

Turn 4 Ends with Alamo Besieged by Texans |

|

|

|

Turn 5 (November 7) -

Siege of the Alamo Begins, Battle of Nueces

Crossing.

This time the Mexicans gain initiative with 2

CPs, while the Texans also have 2 (one of which is unused).

The Mexicans decide to abandon the effort to attack Goliad, which is

now too well defended with two units inside, and to instead respond to

the threat to San Patricio (and possibly even Laredo). The

Mexicans make two moves: 1) the Lipantitlan cavalry is pulled back

through San Patricio across the crossing of the Nueces to attack the

Texans at Lipantitlan; and 2) the Alamo cavalry is moved across the

Medina river to Rancho Seguin south of San Antonio to slow any Texan

efforts to get around San Antonio for an attack. To reduce supply

difficulties, the Texans activate Austin and send Seguin and Kimball on

patrol south of the Alamo to Casablanca, while bringing Milam up to the

Alamo. In the Battle of Nueces Crossing, both units engaged are

Bs, so Horton fires first as the defender followed by

Lipantitlan. The Texans score a hit, while suffering no loss, and

the reduced Mexican unit retreats back to San Patricio. At the

Alamo, the Mexicans initiate a cannonade with Cos (2 steps) firing, to

which Austin (2 steps) replies with counterbattery. Neither side

suffers any losses. The Texans face some supply difficulties with their

main army at the Alamo (1 unit over supply limits), but the Mexicans do

not. The Texans receive Travis (1 step) as a reinforcement at

Gonzales.

Travis is not yet a

brigade

leader historically in

1835, but the commander of an independent cavalry force. However,

he was an aggressive revolutionary figure from the outset. After

the Battle of Concepcion, Travis was sent out on various independent

scouting missions with Texan cavalry and Austin made him a

Captain. He often worked with Seguin, patrolling to the west of

San Antonio to intercept Mexican supplies and reinforcements.

Later, on Dec. 20, Travis became a Lieutenant Colonel commanding the

Texan Regular Cavalry, and over the winter succeeded to the post of

co-commander of the Alamo (along with Bowie, chosen by the volunteers)

by default, after the original commander of the Texan garrison, Lt.

Col. James Niell, left on leave. The Battle of Nueces

Crossing historically took place near the end of the previous week, on

Nov. 5, between Westover’s dragoons and the Mexican troops under Capt.

Don Nicolas Rodriguez that had formed most of the garrison of

Lipantitlan, the 2nd Active Company of Tamaulipas, with 60 Mexican

soldados, and 10 Irish irregulars from San Patricio. The Mexicans

had lost 27 other men from their company captured by Westover’s men

when Lipantitlan was taken, along with 2 guns. At the

Battle of Nueces Crossing, Capt. Rodriguez, after realizing that he had

been outmaneuvered by Westover, tried to return and recapture his post,

but was beaten back with a loss of between 17-42 men killed, wounded

and missing, while the Texans suffered only 1 man

wounded.

| 1835

Turn 5 Movement |

1835

Turn 5 End |

|

|

Turn 6 (November 14) -

Texan Desertions At the Alamo Siege.

The

Mexicans use a Runaways event against the Texans’ main army at the

Alamo siege, giving them only 1 CP but providing initiative over the

Texans, who have 3 CP. The Texans suffer one-step losses in

several of their besieging units, including the Militia and

Milam. The Mexicans make 1 move: they withdraw their damaged

Lipantitlan cavalry back to the safety of Matamoros, planning to

rebuild its strength there. The Texans make 3 moves: 1) Travis

moves from Gonzales up to the Alamo; 2) Bowie moves from the

Alamo down to Casablanca to reduce supply difficulties; and 3) Horton

moves from Lipantitlan into San Patricio. At the Alamo, the

Mexicans initiate a cannonade with Cos (2 steps) firing, to which

Austin (2 steps) replies with counterbattery. Neither side

suffers any losses. Indeed, with the Texan desertions, a Mexican

sally or attack from San Antonio might have managed to break the siege

at this time, but the Mexicans are not confident of their prospects for

attacking the Texans after their poor performance at the Battle of

Concepcion. The Texans face some supply difficulties with their

main army at the Alamo (1 unit over supply limits), but the Mexicans do

not. The Texans receive New Orleans (3 steps) as a reinforcement

at Linnville.

At this time,

historically, the

Texan Army under

Austin at San Antonio, which had reached a strength of about 700-800

men in early November, was reduced to only a little over 400 men by

desertions. By the time of the attack on San Antonio, it had been

rebuilt somewhat to 500 men, but never regained its maximum

strength. The Texan Army at this stage of the campaign was

notoriously ill-disciplined, men coming to join up or leaving the ranks

much as they pleased. Boredom and illness were more of a danger

to the Texans’ strength in 1835 than were the Mexicans. The New

Orleans unit that appears in Nov. 1835, the “New Orleans Greys,” (so

named for their obsolete grey U.S. Army uniforms), is really the first

of two that fought in the Texan Revolution. The surviving men of

this unit historically were incorporated into various other units over

the winter, and the second New Orleans unit that appears in Velasco at

the start of the 1836 scenario represents further volunteer

reinforcements from the same city that arrived in January.

Several other interesting events took place at this time.

There was a skirmish between a Texan navy ship and a Mexican warship

off Matagorda, fighting over the military supplies aboard a beached

Texan supply ship. Off-map, the federalist Mexican leader

Jose Mexia, allied with the Texans, tried to invade the Mexican port of

Tampico south of Matamoros with 150 men, the so-called “Tampico Blues,”

but this scheme was defeated by Santa Anna’s centralist forces and many

of Mexia’s men were captured and executed, a sign of things to

come.

| 1835

Turn 6 Movement |

1835

Turn 6 End |

|

|

Turn 7 (November 21) -

The Grass Fight.

The Texans have

initiative with 3 CPs, while the Mexicans have only 2 CP. The

Texans make 2 moves: 1) New Orleans is moved up to Espiritu Santo from

Linnville; 2) Austin is activated and sends Travis, along with Seguin,

around to the south of San Antonio below Rancho Seguin to threaten San

Antonio from the west (and also possibly Laredo or Presidio Rio

Grande), and spread his forces out to reduce supply difficulties (these

two cavalry units are the best choice for such an independent mission

as they are As and can readily retreat from any attacking Mexican if

properly positioned), while also bringing Bowie up from Casablanca

through the Alamo (because the Alamo is still under siege Bowie can

pass through this hex) and across the ford to Rancho Seguin, and

sending Kimball across the ford to Rancho Seguin as well.

The Texans also use 1 CP for forage to replace the step loss suffered

by Milam. The Mexicans respond by sending the San Antonio

infantry to reinforce their Alamo cavalry at Rancho Seguin, and use

their remaining 1 CP to provide a step to their Lipantitlan unit by

forage. In the Grass Fight that follows, the Mexican Alamo

cavalry (B) fires first, followed by Kimball (B, attacking), and then

Bowie (C) in the first round, while the Mexican infantry (C), arriving

in the second round of combat, would fire after Kimball but before

Bowie as a defender. The Texans suffer no losses, while the

Mexicans suffer a 1 step loss to their cavalry in the first round, and

decide to retreat back to San Antonio in the second round, suffering no

further losses. At the Alamo, the Mexicans initiate a cannonade

with Cos (2 steps) firing, to which Austin (2 steps) replies with

counterbattery. Neither side suffers any losses. The

Texans no longer face supply difficulties with their main army outside

the Alamo, down to 3 units, nor do the Mexicans. The Texans

receive Burleson (3 steps) as a reinforcement at

Gonzales.

Discontent with Austin’s

leadership style by

this point was so great, with Houston intriguing against him back at

San Felipe where the Texan provisional government was meeting, that

Austin received orders by November 18 relieving him of command and

directing him to assume new responsibilities as Texas’s representative

to the United States seeking recognition and help, an assignment better

suited to his talents. Austin considered an assault on San

Antonio before relinquishing his command, but was deterred by Lt. Col.

Edward Burleson and the other officers, and he finally left on November

24. After his departure, the Austin block represents a

combination of the Texan artillery assembled by that time, and

Burleson’s authority as the newly elected CinC. Burleson had been

involved with the revolution from the start, and participated in the

initial battle of Gonzales as one of the several Texan leaders, but he

now assumes command for the first time as the Texans’ elected General

(in 1836 he reverts again to a regimental Colonel after Houston takes

command). In the Grass Fight, which historically took place

on November 26, Bowie with about 140 men including 40 cavalry was sent

to intercept a Mexican supply train escorted by cavalry, a total of

about 150 defenders initially, which was then reinforced with troops

from San Antonio. The Mexicans suffered substantial losses,

estimated at 50-60 men including 15 dead left on the field, and the

Texans only 5 casualties, including 1 man missing and 4 wounded (one of

whom had a headache from a Mexican musket ball that bounced off his

head!). The Texans took the train, but they were disappointed to

learn it contained not the Mexican army’s paychest, but only “grass,”

fodder for the Mexicans’ horses and oxen.

| 1835

Turn 7 Movement |

1835

Turn 7 Battle south of San Antonio

|

|

|

1835

Turn 7 End

|

|

|

|

Turn 8 (November 28) -

The Assault on San Antonio Begins.

The

Texans have initiative with 3 CP, while the Mexicans have 1 CP.

The Texans make 3 moves: 1) Burleson moves from Gonzales up to the

Alamo; 2) New Orleans also moves from Espiritu Santo up to the Alamo,

and force marches across the ford into San Antonio; and 3) Austin is

activated and sends Bowie and Kimball from Rancho Seguin across the

fords of the Medina into San Antonio, while also sending Milam across

the ford from the Alamo into Rancho Seguin and from there up to San

Antonio, and the Militia across the ford from the Alamo into San

Antonio, leaving Austin, along with the newly arrived Burleson, at the

Alamo. In the first stage of the Battle of San Antonio, the

Mexicans choose to withdraw and defend inside the city, accepting

siege, and the Texans storm the city. The Mexican Alamo artillery

fires first (A), followed by Milam (B), then the Alamo cavalry (C

defending inside a siege, and down a step from the Grass Fight to 1),

the San Antonio infantry (C), and then the New Orleans infantry, Bowie,

and Militia (Cs, with New Orleans down a step to 2 from force march

attrition and the Militia still down a step to 1) and Kimball (also a C

storming a city). All 5 Texan units can participate in storming

the city as the storming limit is 6 for a city. The Texans have 8

steps attacking against the 7 steps of defending Mexicans.

The

Mexicans have double defense fighting inside the city, as do the Texans

attacking it. In a two-round battle, the Mexicans lose a step

from their artillery and a step from their infantry, while the Texans

also lose 2 steps, from Milam and New Orleans. The Texans

withdraw as of the third round, maintaining the siege. At the

Alamo, the Mexicans initiate a cannonade with Cos (2 steps) firing, to

which Austin (2 steps) replies with counterbattery. Neither side

suffers any losses. The Texans face supply difficulties at

San Antonio, with 5 units there, Austin, Bowie, Milam, New Orleans, and

the Militia (3 units over supply limits), but not at the Alamo, with

only Austin and Burleson there, and the Mexicans in San Antonio and the

Alamo do not have supply difficulties. The Texans receive Grant

(2 steps) as a reinforcement at Goliad.

At this time, Burleson

nearly

abandoned the

siege of the Alamo, on December 4 reaching a decision to do so and

retreat to winter quarters, which was supported by most of his

officers. However, two officers, Milam and Col. Frank Johnson,

strongly opposed the decision, and a compromise was reached allowing

Milam to ask for volunteers to attack the town. Calling out, “Who

will follow old Ben Milam into San Antonio,” he gathered a force of

about 300 volunteers for the attack, out of the 500 men remaining in

the Texan Army near San Antonio at the time, beginning the attack on

the city on December 5. The entry of Texan reinforcements

in the late game necessarily accelerates forces that flowed into Texas

or assembled during late December and January, for game purposes.

For example, Dr. James Grant was involved in the fighting at San

Antonio, but after the battle he and Johnson took charge of the

so-called “Matamoros Expedition,” an abortive effort to march on Mexico

and take the port of Matamoros before the Mexicans could reinforce

it. Historically, the governor of Texas issued orders for this

expedition on Dec. 17 to Houston, while the governing council ordered

Johnson to command it. Grant also declared himself acting

commander, and on January 1, 1836 left San Antonio with 200 men heading

for Goliad, leaving behind only a small garrison of 120 men under Lt.

Col Neill (represented by Bowie and the Alamo artillery after the

Texans take control of the Alamo), while Travis, commanding the Texan

regular cavalry, returned to San Antonio and added another 30 men to

the

garrison.

| 1835

Turn 8 Movement |

1835

Turn 8 Battle of San Antonio begins

|

|

|

| 1835

Turn 8 End |

|

|

|

Turn 9 (December 7) -

The Fall of San Antonio.

The Texans

use a Deguello event, giving them only 1 CP but gaining initiative over

the Mexicans with 2 CPs (one of which goes unused). The

Texans move Grant from Goliad to San Patricio, covering it against any

Mexican attempt to reclaim the city. The Mexican Garza Tejano

cavalry at Refugio moves back to Carlos, now that the prospects for

recovering San Patricio are diminished (in the campaign game, this unit

will disband and return with Urrea in 1836 if not killed, and this gets

it out of harm’s way by not requiring the Texan to attack it to control

Refugio). In the Battle of San Antonio, the Mexicans have 5 steps

left, and the Texans 6. The Mexican Alamo artillery again fires first

(A), followed by Milam (B), then the Alamo cavalry (fighting as a C

inside the city), then the San Antonio infantry (C), and then the New

Orleans infantry, Bowie, and Militia (Cs). In a brutal

three-round battle, the event card enabling the Texans to attack for

more rounds than usual, the 5 remaining steps of the three defending

Mexican units are eliminated, except for the last step of the artillery

which is captured and converted into a Texan artillery unit after the

other Mexicans are eliminated, but the Bowie infantry loses a step

(bringing all the Texan units down to 1 step each) and Milam is then

eliminated (in game terms, the Texan chooses him to die on the third

round to satisfy another pair of hits inflicted by the Mexicans, as he

has already fired that round and the Texan wants all of his C units to

be able to fire and finish off the Mexicans). The Texans regroup

and send the Kimball cavalry back to Rancho Seguin. The Mexicans

then sally from the Alamo (the Texan controlled the order of battles so

that the attack on San Antonio was resolved first), with Austin (B)

firing first, then Cos (also B, but attacking), then Burleson (C), and

finally Morelos (C, down a step from losses at the battle of

Concepcion to 3). The Texans choose to retreat into San Antonio

after a round of battle to join the rest of their army, though

suffering no losses. Neither side faces any supply difficulties

now, with 6 Texan units in San Antonio and the Mexicans temporarily

able to receive reinforcements and supplies from outside the

Alamo. The Texans receive Ward (Georgia) as a reinforcement at

Linnville.

| 1835

Turn 9 Movement |

1835

Turn 9 Battle of San Antonio continues

|

|

|

| 1835

Turn 9 End |

|

|

|

Turn 10 (December 14) -

End of the Campaign, Cos Surrenders the

Alamo.

The Mexicans get initiative with 4 CP, while the

Texans also have 4 CPs. The Mexicans choose to forage to

rebuild losses to their units in the Alamo (1 step for Morelos, with

the other steps going unused) as they do not have a realistic hope of

retaking San Antonio, San Patricio or Goliad. In game terms, the

inability to use the other steps reflects the uselessness of most of

the reinforcements that Ugartechea brought, but getting initiative this

turn was key for the Mexicans to be able to forage at all before the

Texans returned to resume the siege of the Alamo. The Texans: 1)

activate Austin and send most of the Texan forces in San Antonio into

the Alamo across the available fords, including Austin, Burleson, New

Orleans, and the captured Alamo artillery, leaving Bowie and the

Militia in San Antonio, 2) move Travis and Seguin from their position

south of Rancho Seguin up to the Alamo by way of Casablanca; 3) move

Ward from Linnville to Refugio (force march); and 4) take a step of

forage as replacements for a damaged unit at San Antonio (Bowie).

The Mexicans could attempt to fight in the open to prevent the Alamo

from coming under siege, but the odds are against them, with 6 steps in

the Cos and Morelos units against 9 Texan steps that have the edge in

fighting quality, so they withdraw inside and accept siege (in a

campaign game, this is probably the better strategy as a surrender at

the end of the 1835 scenario rather than a last-ditch battle in the

open will only cost the Mexicans Cos, who could still appear as a

replacement for another leader as he was not killed, but will preserve

the more valuable permanente Morelos battalion to return in 1836 as it

was also not killed - in the 1835 scenario alone, the Mexican could try

his luck fighting outside to prevent a siege of the Alamo, but would

likely lose his men as well as the game). The Texans face supply

difficulties at the Alamo with 6 units there (3 units above supply

limits), though the Mexicans do not. The Texans receive Houston

(2 steps) as a reinforcement at San Felipe. The Mexicans surrender the

besieged Alamo at the end of Turn 10.

Cos agreed to surrender

on

December 10, after the

fall of San Antonio, and was given a week more for his troops to depart

for Mexico under parole not to fight again, actually leaving on Dec.

14. Cos had 1100 men at the time of the surrender with

Ugartechea’s reinforcements, but left behind sick and wounded and

suffered from attrition marching across the desert, so that by the time

his remaining forces reached Laredo on Dec. 25, they were reduced to

800 men. Cos had proudly declined help from the Texans. The

20 guns of the Mexican artillery, including those already captured in

the fighting in San Antonio, were of course relinquished to the Texans,

apart from one gun Cos was allowed to take for protection against

Indians. Santa Anna compelled Cos to break his parole, and

he and the permanente Morelos battalion fought again in 1836, though

Cos no longer had brigade command. Houston historically became

Texan CinC under the authority of the provisional government in late

November, though he still did not have command over the main Texan army

that had been led by Austin. He did not go to the front in these

circumstances, and his authority was not finally confirmed until early

March 1836, after the Texan government declared independence from

Mexico.

| 1835

Turn 10 Movement |

1835

Turn 10 Texans besiege Alamo again

|

|

|

| 1835

Turn

10

Cos

Surrenders

the

Alamo |

1835

Turn 10 End game |

|

|

The Texans, in control of San Antonio, San Patricio, Goliad, and the

Alamo (which comes under their control after the Mexicans surrender the

besieged fort at the end of Turn 10 and depart), are the winners, as

the Mexicans have failed to hold the minimum of four Mexican-friendly

towns they needed to win; they only have the three Mexican holding

boxes along the Rio Grande, which the Texans never attacked so that the

Presidial garrison troops were never activated. After the

end of the campaign, the Texan receives Wallace as a reinforcement at

Goliad. Wallace’s Lafayette battalion contained troops from U.S.

volunteer units such as the New Orleans Greys, and former Texan members

of the Matamoros Expedition who had abandoned it to join Fannin at

Goliad. During the winter, there is some reorganization of the Texan

army, with new reinforcements arriving from the U.S. and other

volunteers and militia going home, to reappear again in the spring when

Santa Anna’s army threatened the reconquest of Texas. Davy

Crockett arrived in San Antonio from Tennessee with his small band of

13 mounted volunteers in early February, joining with Bowie’s

men. Meanwhile, Gen. Sesma’s Vanguard Brigade arrived in Laredo

on December 26 to join forces with Cos, later moving up to Presidio Rio

Grande to join with the rest of Santa Anna’s forces. From

Saltillo in northern Mexico, where Santa Anna’s main army was assembled

on January 24, the Mexicans set out in stages across the desert due to

the limited supplies, headed for the Rio Grande, while Urrea and his

cavalry left Saltillo in another direction, moving down to Matamoros in

late January and combining there with the Yucatan battalion before the

Matamoros Expedition could get under way from San Patricio, dooming the

possibility of an invasion of Mexico. The Texans began to receive

reports in mid-January of the advance of Santa Anna’s army, though most

still considered a winter campaign across the desert by a large army

implausible. Nevertheless, Santa Anna’s soldados made the march,

though suffering en route from winter storms and from frequent raids by

Comanches on their supplies and stragglers. Finally, on

February 16, 1836, Santa Anna with his Vanguard Brigade began its

crossing of the Rio Grande and the invasion of Texas was

underway.

Click

here to order Texas Glory now.

|

|