The 5th edition of this classic wargame brings the game back to its 1st edition roots with some improvements. Napoléon can be played by two, three, or four players using the new Grouchy block.

Read what gamers are saying about Napoléon on BoardgameGeek.

On June 18, 1815, one of the most decisive battles in military history was fought in fields ten miles southeast of Brussels. Within a short 100 days, Napoléon, former emperor of France, had returned from exile on the island of Elba, again seized power, quickly assembled an army, and marched to attack the dispersed British and Prussian armies now preparing to invade France.

Napoléon attacked on June 15th, defeated the Prussians at the Battle of Ligny on the 16th and after a day of pursuit, faced the British and Dutch army commanded by Wellington. Aided by superb defensive tactics and the timely arrival of Prussian reinforcements, Wellington defeated the French in the great Battle of Waterloo, ending forever the military ambitions of the great Napoléon.

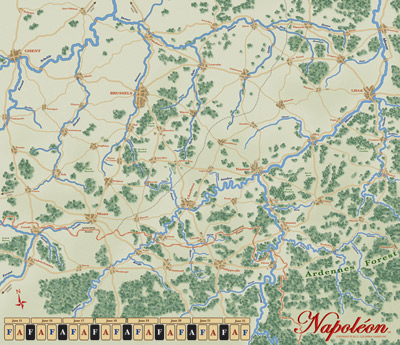

(Click to expand the map)

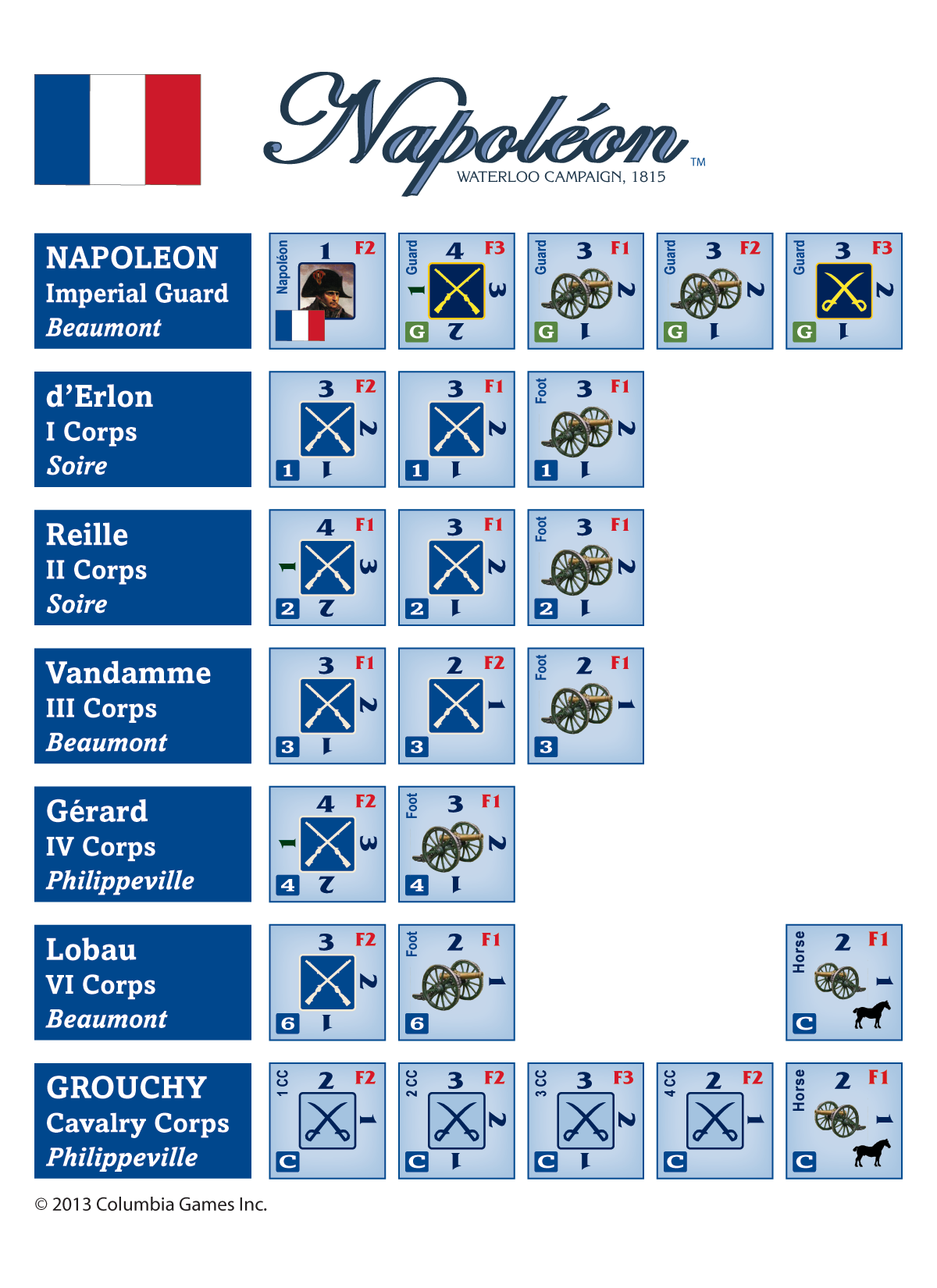

(Click to expand the French order of battle)

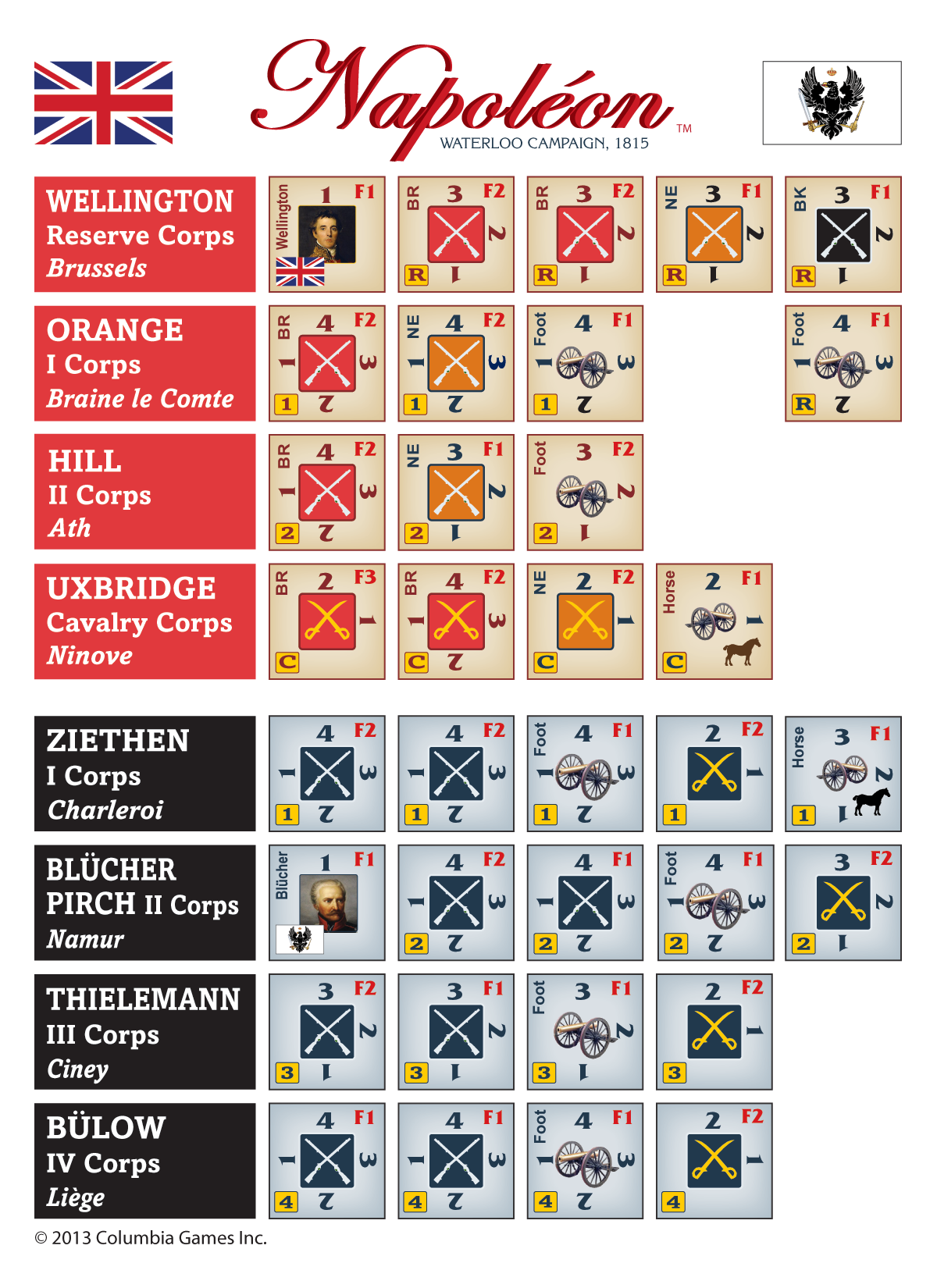

(Click to expand the Allied order of battle)

Watch the Kickstarter video about Napoleon.

History of the Waterloo Campaign

The Eagle Returns

In March 1815, while delegates at the Congress of Vienna, wined, dined, and danced, and in between, wrangled over the future of Europe, Napoléon Bonaparte, the reason for their celebration, escaped from exile. Less than ten months had passed since the French Emperor had surrendered to the invading Allies (Russian, Prussia, Austria, and Britain) and accepted exile on the small island of Elba. The Allies were naive to think this Lilliputian nest would satisfy the ambition of a man who had dominated France and much of Europe for fourteen years.

In addition to the reactionary squabbles of the Allies in Vienna, Napoléon's gamble to return to France depended on reports he received of growing unrest at home. Public opinion, at first impressed with the novelty of peace under the restored Bourbon, Louis XVIII, had quickly turned sour. The peasants had rightly become suspicious that they might lose their lands to the returning aristocracy. The once mighty Grand Armee in particular had not fared well. Much of it had been disbanded; thousands of officers were on half-pay, and once proud veterans found themselves idle in a society that had no place for them. They soon forgot the mud, the hunger, the suffering of Napoléon's campaigns and remembered only the glory.

Napoléon landed in southern France near Cannes with about one thousand loyal supporters and began a march to Paris. He had lost none of his charisma and the closer he got to the capital city the more popular he became. Peasants welcomed him as their champion. Troops sent to arrest him, including Marshal Ney who had betrayed him the year before, defected to his side. The royal court, unable to check the advancing Napoléon and sensing the public mood, fled into exile in Belgium. Napoléon re-entered Paris in triumph with a bloodless coup d'etat.

The 100 Days: Opening Moves

Napoléon did not believe for a moment that the Allies would accept his return to power without a fight. He attempted to buy time by sending envoys with offers of peace to the Allied powers. Far from accepting this fait accompli, the Allies put aside their differences and declared him an outlaw, the "General Enemy of the World". On March 25th, Austria, Britain, Russia, and Prussia signed a formal alliance. They would invade France again; the famous One Hundred Days' Campaign had begun.

In theory, the military power of the Allies was awesome; their combined armies totalled close to one million men. Wellington, leading 110,000 British, Dutch, and Belgian troops, would attack from Brussels. From Liege would march a Prussian army of 120,000 commanded by Blücher. An Austrian army of 210,000 would invade across the Rhine, supported by 150,000 Russians further south. And, finally, a mixed army of 75,000 Austrians and Italians planned to attack southern France along the Mediterranean coast. Napoléon could muster less than 200,000 men, but he had overcome such long odds many times before.

May drew to a close with only the forces of Wellington and Blücher in position. Russia and Austria would be along shortly, but not until July. The question for Napoléon was simple: attack or defend? Although his strength was growing daily, and was aware of the advantages of a defensive campaign, he also knew that time favored the Allies. Napoléon concluded that a surprise invasion of Belgium and the quick defeat of the Anglo-Dutch and Prussian armies there might give him a decisive victory. This would rally the French people to his side, and probably cause the collapse of the Tory government of Britain, putting the Whigs, who were more inclined to peace, in power. Napoléon would then be free to deal with the Russians and Austrians, two armies he had beaten several times before.

The French Invasion

Early in June Napoléon ordered the Armée du Nord, composed of 89,000 infantry, 22,000 cavalry, and 9,000 artillerymen with 366 guns, to concentrate on the Franco-Nederlands border. Napoléon knew that the Anglo-Prussian armies were both scattered throughout the countryside. Following his classic "Strategy of Central Position", he intended to mass his army at the junction of the two forces, wedge the French troops between them, and then defeat each in turn. By June 14th, unknown to both Allied commanding generals, Napoléon succeeded in concentrating his army at the frontier town of Beaumont. It was a brilliant opening to the campaign.

Now the Prussian commander, Blücher, played a dangerous game. On June 14th his outposts along the French border reported the lights of hundreds of bivouac fires near Beaumont. He immediately ordered his four corps to concentrate at Ligny, covered by Ziethen's I Corps at Charleroi. Few maneuvers are as risky as concentrating in a forward position against a capable opponent. Against Napoléon it should have been fatal.

Soon after 3 a.m. on June 15th, the French confirmed their presence. Three great columns of men, centered on Soire, Beaumont, and Philippeville, crossed the border and converged on Charleroi. Napoléon expected this town would be in French hands by noon. It wasn't. Because of delays in staff work, confused marching orders, and the unexpected resistance of Ziethen's Corps at the River Sambre, the town was not taken until late in the afternoon.

Meanwhile, Wellington, commander of the Anglo-Dutch army, who had built himself a formidable reputation fighting the French in Spain, also erred. He never thought Napoléon would take the offensive, but just in case, firmly believed the best French strategy would be to advance along the Mons-Brussels road and threaten the British communications with the coast. Consequently, he had deployed his polygot "infamous army" to cope with this threat. When Wellington received early reports of a French invasion, he ordered this army to concentrate at Hal to cover the Mons-Brussels road, convinced the reported advance on Charleroi was a feint. He realized his mistake only after confirmation of the French capture of Charleroi. Declaring "I've been humbugged", Wellington ordered his army to march to Quatre Bras.

Fortunately for the Allies, the French made their own share of errors. Marshal Ney, a capable but impetuous leader, commanded the Left Wing (I and II Corps) with orders to seize the crossroads at Quatre Bras. Marshal Grouchy, an excellent cavalry commander, controlled the Right Wing (III and VI Corps) and his job was to push the Prussian I Corps back to Ligny. Leading the advance, both men directed their respective forces with more caution than the situation warranted. Although guarded only by a few thousand footsore Anglo-Dutch troops, Quatre Bras was not taken that day. Napoléon, who retained direct control of the Reserve (VI Corps, Imperial Guard, and Cavalry Reserve) and furious with the slow progress of his army, had no choice but to mutter the night away just north of Charleroi.

Quatre Bras & Ligny

Napoléon still had the advantage. On the morning of the 16th, he found the Prussian army (minus the IV Corps still marching from Liege) lined up for battle near Ligny, and the army of Wellington nowhere in sight. The Allies had blundered into the very situation he desired: an opportunity to defeat one army at a time. Ney was ordered to advance the Left Wing and seize Quatre Bras; Napoléon and Grouchy would fall on the Prussians at Ligny. Ney was then to attack the Prussian flank at the critical moment from Quatre Bras.

Ney never did manage to achieve his relatively simple task. Some Anglo-Dutch troops had arrived at Quatre Bras during the night, but early in the morning, the French still outnumbered them by about three to one. Ney did not advance until just before Noon, and then proceeded cautiously, well aware of Wellington's known tactics of keeping large bodies of men hidden behind a rise. This slow advance allowed Wellington to arrive with ever increasing reinforcements, compounded by the fact that Ney's II Corps which he had ordered to maneuver for a flank attack on Quatre Bras never arrived. The commander of that corps, Reille, received confusing orders from Napoléon which suggested a march to reinforce Ligny and off he went in that direction. Ney angrily counter-manded the order, with the result that the II Corps spent the day marching back and forth between Quatre Bras and Ligny, but never fought in either battle. In any event, by late afternoon, Wellington at Quatre Bras now outnumbered Ney. The French attacked ferociously until night fell, but without success. The Battle of Quatre Bras ended as a tactical stalemate, and Ney never did get to attack the Prussians at Ligny.

Without Ney's support, Napoléon found the Prussians at Ligny to be more of a problem than he expected. Blücher had taken up a position which exposed many of his 83,000 men to the superior French artillery. But badly written orders given to the 78,000 French troops cancelled that advantage. Fortunately, the skill and stamina of Napoléon's veterans was enough to overcome the unseasoned Prussians. After hours of bitter fighting, during which the hamlets of Ligny changed hands several times, Napoléon unleashed his Imperial Guard after Blücher had committed all his reserves. In a thunderstorm, the Guard smashed through the Prussian center, followed by hordes of French cavalry. The Prussian army collapsed into rout, but was saved by the falling darkness since effective pursuit was impossible. Still, Napoléon had won a great victory, and a similar defeat for Wellington next day looked certain.

That night, Napoléon formed his plan for the next day. He would give Grouchy and his two corps the task of pursuing the Prussians to keep them disorganized and away from Wellington. Ney would attack and pin the Allied force at Quatre Bras while Napoléon descended on their flank from Ligny. A simple plan, perhaps too simple, a plan that would self-destruct because of French sloth.

During the night, the Prussians decided to regroup at Wavre and then retreat towards Liege. Blücher, who had become separated from his main force and nearly killed, arrived on the scene to alter this plan. He ordered that the army would regroup at Wavre as planned, but from there would march west to link up with Wellington at Waterloo. Blücher's inspired decision was the turning point of the campaign and is all the more remarkable considering the shattered morale of his badly-battered army.

June 17th saw an overconfident Napoléon lose the chance of victory. Learning of the Prussian defeat, Wellington realized he must retreat from his exposed position at Quatre Bras. He began to withdraw during the night towards Waterloo and was in full retreat the next day. But while this was happening, Napoléon spent the morning inspecting the battlefield of Ligny and expounding on the horrors of war to his assembled staff. Ney also seemed to feel no sense of urgency. He had received an ambiguous order from Napoléon which did not make it clear he should attack and pin the Anglo-Dutch army.

Just before noon Napoléon finally dispatched Grouchy to pursue the Prussians and began to move himself on Quatre Bras. He was infuriated to learn that Ney had not engaged the enemy and personally led the cavalry in hot pursuit of Wellington. This might still have seriously disrupted the Anglo-Dutch army and made another victory possible, but a cloudburst slowed this late pursuit and allowed Wellington to make an orderly withdrawal with only a few minor skirmishes.

The Battle of Waterloo

The stage was now set for the great battle to be fought just south of Waterloo at Mont St. Jean. Sunday, June 18th, dawned with Wellington arrayed along the rise of Mont St. Jean. He had chosen this ground well; most of his men were deployed behind the slope of his rise, and a shallow valley of ripe wheatfields separated the two armies. The British commander had 50,000 infantry, 12,000 cavalry, and 156 guns. Napoléon had 49,000 infantry, 16,000 cavalry, and 246 guns. Grouchy with 30,000 French troops was in pursuit of the Prussians, convinced he had them had running and sent a message to Napoléon advising him of this. But the Prussians had already regrouped at Wavre and having advised Wellington they would come to his aid began their fateful march towards Waterloo. Wellington had also positioned Prince Frederick at Hal with 17,000 men and 30 guns in case Napoléon should attempt to turn that flank.

By now, almost predictably, the French dallied away the morning. Napoléon, unaware that Blücher drew closer every minute, delayed the opening of the attack in order to allow the ground to dry and provide a better surface for his guns, and better footing for his cavalry.

By now almost predictably, the French delayed their move. With Blücher drawing closer every minute, Napoléon was inspecting the troops and had decided ground to dry and provide a better surface for the guns. Wellington, meanwhile, had chosen his ground well: his men were behind a slope and his flanks covered.

At 11:30 am Napoléon sent Prince Jerome to create a diversionary attack on Chateau Hougoumont on Wellington's left. Unfortunately, the Prince was determined to maintain his family honor by seizing the Château, and called for reinforcements until most of Reille's III Corps was tied down by a small defending Allied force.

Napoléon ordered the artillery to start firing at 1:00 pm and 30 minutes later d'Erlon made a direct attack on Wellington's centre. Napoléon intended to crush the Allies with a series of frontal assaults. This first attack was checked by the British cavalry but in their enthusiasm they swept-on into the main French ranks and were decimated by a counter-charge. Napoléon now ordered Ney to capture Wellington's forward position on the crest at La Haie Sainte. Ney, an unreliable tactician, mounted a cavalry attack in the mistaken that the Allies had begun to retreat. The scale of the attack grew out of all proportion, until 5,000 cavalry were aimed at the Allies. However, they were unsupported by any infantry or artillery and the British, far from being in retreat, formed squares. The artillerymen left their guns and sheltered in nearby squares when the cavalry came close. The French cavalry could only wheel around the squares; they had no infantry support nor horse artillery available to fire on the squares. Finally, under the heavy fire, they were forced to withdraw.

Meanwhile, the first Prussian units were arriving on the eastern flank of the French. Napoléon sent the Young Guard to meet them. Realizing that Ney would have to be supported, Napoléon sent Flahaut and Kellerman to his aid with their cavalry. Once again, the cavalry attack got out of hand. This second attempt failed, but the British squares only just survived the assault. Ordered by Napoléon to attack again, Ney finally changed his tactics and launched a co-ordinated attack of cavalry, infantry, and artillery which was completely successful. Wellington's center could be smashed if more troops could follow up the French advantage. Wellington himself, realizing his danger, committed his reserve, brought in troops from his right wing, and personally commanded the center.

Ney appealed to Napoléon for reinforcements. By now, however, the Prussians were presenting a serious threat on the east and Napoléon sent some of his Guard to face them. Apparently, he did not believe Ney's assessment of his situation, and this mistake cost him probable success. Although the Guard acted quickly to stabilize the position of the French right flank and returned into reserve, this short respite enabled Wellington to strengthen his weak center and allowed Ziethen's Corps to arrive and support the Allied left.

Napoléon finally ordered his Imperial Guard into action in the centre at 7:00 pm. The Allied forces had been commanded by Wellington to lie down behind the banks of the Ohain road, and one column of the Guard was stopped and turned back by the sudden appearance and close range fire of these troops. When the French advance was halted, Wellington ordered all troops to attack with bayonets. There were heavy casualties on both sides, but the French finally fell back. News that the Guard was in retreat demoralized the remaining troops and realizing that the Prussians were at their rear, the French army turned and ran. Only the Guard achieved an orderly withdrawal.

Aftermath

The French flight continued until Napoléon was able to rally his men in Philippeville. Knowing he would have to return to Paris to restore public confidence in him, he left Soult to organize a defensive campaign. Grouchy, meanwhile, heard of the main army's defeat the next day. He retreated to Philippeville by way of Namur, successfully holding off the pursuing Prussians.

The French position after Waterloo was not hopeless. Both sides had lost heavily during the campaign; the Allied losses amounted to nearly 55,000 men and the French losses to 60,000. There were still about 170,000 troops available to bar the way of the Allies into Paris; while after making necessary detachments to cover important French fortresses the Allies had about 118,000 men to advance on Paris.

Schwarzenberg, advancing across the Rhine, was checked by Rapp at the battle of La Souffel, and it seemed quite possible that France itself could be held. Napoléon had attempted to place all the blame for defeat on his subordinates. Undoubtedly their incompetence had been a contributing factor but Napoléon himself was guilty of many errors of judgement including underestimation of his opponents. Now, although he might have persuaded the people to fight on, the Chamber of Deputies would no longer support him. Napoléon hesitated to control them by armed force, and so they were able to call the National Guard to their protection and demand Napoléon's abdication. On June 22nd he abdicated in favor of his son and retired to Malmaison.

The Allies became strung out during their advance on Paris. Napoléon offered his services as a general but was refused. The government would agree onIy to place the service of a frigate at his disposal. Napoléon set out for the vessel at Rochefort in the hope he could escape to the United States. He found there that a British naval squadron lay off the port and that Louis XVIII had ordered the city authorities to arrest him. He finally agreed to board HMS Bellerophon, hoping the British would allow him to go to America or to settle in England. He was sent instead to exile on the remote island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, where he died six years later in 1821.